At the Fall Semester of the inaugural Outer Coast Year, faculty member David Egan taught his philosophy class, Humans and Other Animals.

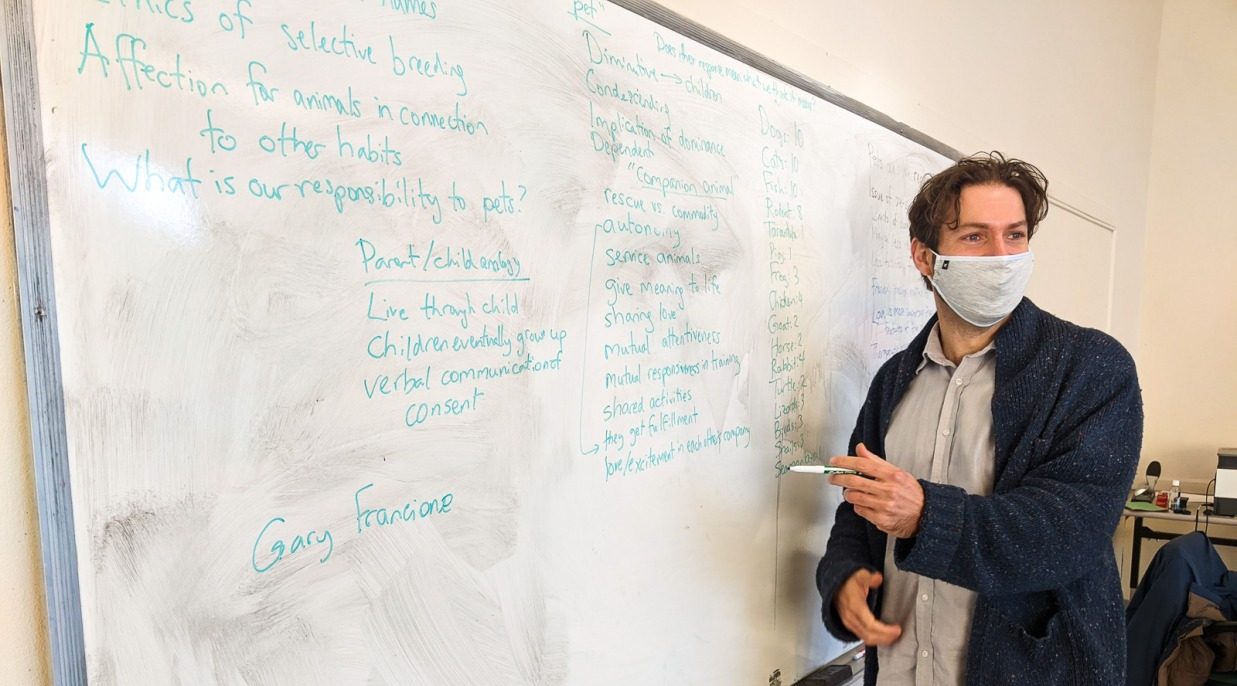

On a sunny Tuesday morning in the classroom, David stood at the whiteboard with Expo marker in hand. Window-warmed sunlight beamed into students’ squinting eyes. As always, the first debate of the day began with a question. Today’s inquiry: Should human-animal relationships be considered friendships?

Energized discussion swelled, whizzing between topics of non-verbal communication, dependence, and dominance. David wrote each new concept on the whiteboard, and a list of moral factors for animal friendship ballooned in front of the class.

The Student Body seemed to edge towards consensus: friendship requires mutuality, and since humans don’t know what animals are thinking, our relationships with them must be more like companionship. Ella (a student from Anchorage, AK) countered: “My dog and I are friends. I love her more than anything. It doesn’t really matter what she thinks.”

David added ‘sharing love’ to the list. Some of Ella’s peers were compelled, and the debate continued.

In November 2020, David’s philosophy-meets-biology course, Humans and Other Animals, spent a particularly energizing week considering domestication. What do we make of individual and societal relationships with animals? Is animal breeding and training moral? And, should we even call the animals in our homes ‘pets’?

David’s class was a place for students to consider complex moral questions together, identifying and interrogating their own gut reactions alongside philosophical frameworks, biological facts, and each others’ experiences. Of his approach, David says:

“I see the classroom as something that is alive rather than a place where everyone just sits around and thinks. The goal of philosophy, and of good teaching, too, is not to persuade your point of view — but to make us all see that things are more complicated than they seem. It’s impossible to live in this world without encounters with animals. There are so many ways in which animals feature in our lives. Part of the goal is to make that more visible to students: that our lives are utterly shaped by animals.”

Eddie (Los Angeles, CA) found that each day’s discussions rarely stopped at the end of class, in part because the topics felt relevant to students’ lives. Having conversations about the readings and course material in dorm rooms provided for “closer relationships with the text and also my classmates,” he said.

One text in particular that stood out for Eddie was John Berger’s essay, Why Look At Animals? Eddie explained:

“John Berger argues that animals first came into our lives as mythical symbols that represented moral understanding. We tied these creatures to our original myths — like Greek mythology — as a way to show our closeness to the natural world. Then he argues that over time, we lost that connection because we’ve domesticated a bunch of these creatures.”

Thanks to Berger, Eddie found personal connection to the course in an unlikely place: comic books.

“I’ve grown up reading comic books my whole life, and I love the idea of superheroes. And yet I’ve never really noticed the fact that some superheroes are based on animals (Batman, Spiderman, Antman). In a lot of ways, [superheroes] represent those same values that original Greek gods have: they are characters that represent moral understanding and heroism in our modern pop culture. I found that connection really interesting, because it connected to my personal life.”

For Adonna (Anchorage, AK), the class brought to light both cultural contrasts and resonances between her and her classmates. Adonna is Iñupiaq and Sugpiaq.

“[My peers] don’t always perceive things the way I do. Westerners tend to believe that animals are lesser than humans. In our society and beliefs, we live with them as one. We are equal to them. We have a lot of respect for them. And that’s not the Western perspective.”

Despite those differences, Adonna described how she and her peers found shared touchpoints: “Even if you aren’t Alaska Native, being Alaskan is still a common ground. You’ve been around people who hunt, you’ve tried some of the foods…and when Chuck Miller [Sitka Tribe of Alaska Cultural and Community Liaison] came, [my peers] were able to see another perspective that represented the same thought process, or similar culture, as me.”

Adonna appreciated that David’s class pushed her thinking. “My first time thinking about some of these concepts between humans and animals gives me a better ability to critically think and use my brain in ways that I don’t usually use it.”

Even as the classroom debates were coming to a close, students expected the course’s big questions would remain pertinent, both at Outer Coast and beyond.

“Next time I think about getting a pet, or buying a piece of leather, or eating a burrito from Chipotle, I’ll think twice about the necessity of doing that,” Eddie said. “I want my actions to reflect the actual conversations I’ve had in this class, and I want to be able to question myself when I find myself in those situations.”